Evidence-based medicine and personalized medicine are promising concepts that can save money and make treatments more effective. What is the biggest barrier to putting both concepts into practice?

Helene Schönewolf: I think that there are many big barriers that are preventing patients from receiving an evidence-based and personalized treatment. What I see, when I look at the landscape of digital solutions that are attempting to solve this problem is, that they demand a lot of money to make treatments personalized by hand or that they require a technical solution that demand many competencies.

The words in the term “evidence-based personalized medicine” already explain it: “evidence-based”, so you need people to fully understand what evidence means, how clinical research works, why gathering patient data is so much less effective than clinical data, how to interpret these data statistically, how to translate it from scientific language into medical language and parameters, how to store the data, how to link the data technically. This demands profound scientific, medical, technical, organizational and process knowledge, and all of that must somehow be produced by the same person. Because, if the programmer doesn’t understand half of what the scientist requires as technical parameters, the results can never be complete. And if the scientist doesn’t understand how the doctor requires the science to be represented, the doctor will make mistakes when applying it. Also, both scientists and doctors need to understand how the informational structure and algorithms would need to be constructed, how the doctor needs the software to be presented. This is very complex. That’s why the scientists in our team are also programmers and when they join our team they get intensely medically trained and specialize in one medical field. We aim to have every scientist regularly accompany doctors because they not only need to know about problems theoretically but they also need to get acquainted with how much pressure doctors are under when they work. The goal is an evidence-based and personalized treatment for the patient, so it must not only be absolutely correct and complete, but must not interrupt the workday of the doctor, because he or she has only a little time for each patient.

Jacques Ehret: It is hard to put both concepts into practice because both terms are to some extent antagonists: The stronger the evidence, the more the outcomes are generalizable to the global population. But since it is a statistical approach, the effect on specific patients may be really different from what is expected. The more personalized the medicine is, the less it may suit patients in general, and therefore insights into how safe a treatment is may be lost.

However, both can be put together because they involve different aspects of what a patient needs. In evidence-based medicine it is important to know how likely a treatment is to work on a patient, and what exactly the risks are for the individual patient, statistically speaking. This information can then be personalized for patients so they can choose between the safe treatments the ones that are more likely to work or will work well enough.

The biggest barrier to putting both concepts into practice is that it is hard to find the equilibrium between sufficient evidence and sufficient personalization. It is difficult because there are no rules for that but the combination of knowledge and experience. However, knowledge increases at a rate that no individual can follow. This is what we try to help the doctors with.

"One pill fits all" is today's medicine paradigm. On the other hand the pharmaceutical market is booming, the number of new medicines for the same diseases is growing quickly. Doctors can choose between thousands of drugs and from this point the problems begin: how to make the right decision? If the doctor's intuition is not enough, what could help?

Jacques Ehret: There are over 10.000 conditions according to the ICD-10 classification. New conditions are added yearly, either because they were not known, were misclassified, or even did not exist (new bacteria or virus for example). Some of these conditions have cures, some of them have treatments to alleviate the symptoms, and some of them do not have any relevant treatments.

There are more and more drugs on the market every year. Evidence about established drugs is increasing and therefore the extent of their safety is being updated constantly, sometimes to the point that they have to be withdrawn. Some conditions like cancer and diabetes get new treatments almost yearly. Some conditions are so rare that it is really difficult to design a treatment for them. Furthermore, pills are not the only treatment possibilities there are. Digital therapeutics, plants, lifestyle modifications, chemical exposure also impact many conditions. There are more than 300,000 "health" apps. Hundreds of plants, hundreds of different sports and diets.

We should not forget that science does not know everything about the human body yet. New discoveries lead to new potential targets for new treatments, and new mechanisms to understand so that the treatment is adequate for the patient. I believe that we still have a long way to go until we understand fully the whole human body, and until then we need to aggregate everything that we know about therapies, and adapt it as much as we can to each patient.

What is also difficult, is that there are further parameters to take into account, like patient compliance. Is the patient ready to actually follow the treatment? There are so many things that a doctor has to do within the average few minutes he sees a patient that he needs support. He has to assess what his patient is more likely to do (take a pill, change his lifestyle, use a certain app), and then he should be able to see which one will be most beneficial for his patient.

Helene Schönewolf : These were my questions when I stopped working in pharma and started with Jacques the project RAMPmedical. We thought maybe doctors just need a drug list that is up-to-date. So we built a simple updated drug list with linked authorization information and some further product information from the relevant pharma company. And doctors found that suitable but clearly couldn’t use it to find the right treatment for any patient. And that’s when we understood how complex it is to make therapy decisions. So, in close cooperation with doctors we added more and more information and then we saw ourselves that this becomes a jungle of information.

So, we began working on the structure of information, to make it rapidly usable. Because the doctor definitely needs to know many parameters of the treatment and the patient. That’s why when a patient goes to a doctor and tells him about a treatment that the patient read about on the internet and the doctor doesn’t prescribe it, it’s because the doctor needs to know more about the treatment. To make a therapy decision the doctor needs to know if the treatment is guideline coherent, if the treatment has been tested, if yes, with how many patients, how effective the treatment was, on what scale, how many side effects there were, for whom is it contraindicated, are there interactions with other drugs the patient is taking and much, much more information.

Jacques Ehret: It is hard to put both concepts into practice because both terms are to some extent antagonists: The stronger the evidence, the more the outcomes are generalizable to the global population. But since it is a statistical approach, the effect on specific patients may be really different from what is expected. The more personalized the medicine is, the less it may suit patients in general, and therefore insights into how safe a treatment is may be lost.

However, both can be put together because they involve different aspects of what a patient needs. In evidence-based medicine it is important to know how likely a treatment is to work on a patient, and what exactly the risks are for the individual patient, statistically speaking. This information can then be personalized for patients so they can choose between the safe treatments the ones that are more likely to work or will work well enough.

The biggest barrier to putting both concepts into practice is that it is hard to find the equilibrium between sufficient evidence and sufficient personalization. It is difficult because there are no rules for that but the combination of knowledge and experience. However, knowledge increases at a rate that no individual can follow. This is what we try to help the doctors with.

"One pill fits all" is today's medicine paradigm. On the other hand the pharmaceutical market is booming, the number of new medicines for the same diseases is growing quickly. Doctors can choose between thousands of drugs and from this point the problems begin: how to make the right decision? If the doctor's intuition is not enough, what could help?

Jacques Ehret: There are over 10.000 conditions according to the ICD-10 classification. New conditions are added yearly, either because they were not known, were misclassified, or even did not exist (new bacteria or virus for example). Some of these conditions have cures, some of them have treatments to alleviate the symptoms, and some of them do not have any relevant treatments.

There are more and more drugs on the market every year. Evidence about established drugs is increasing and therefore the extent of their safety is being updated constantly, sometimes to the point that they have to be withdrawn. Some conditions like cancer and diabetes get new treatments almost yearly. Some conditions are so rare that it is really difficult to design a treatment for them. Furthermore, pills are not the only treatment possibilities there are. Digital therapeutics, plants, lifestyle modifications, chemical exposure also impact many conditions. There are more than 300,000 "health" apps. Hundreds of plants, hundreds of different sports and diets.

We should not forget that science does not know everything about the human body yet. New discoveries lead to new potential targets for new treatments, and new mechanisms to understand so that the treatment is adequate for the patient. I believe that we still have a long way to go until we understand fully the whole human body, and until then we need to aggregate everything that we know about therapies, and adapt it as much as we can to each patient.

What is also difficult, is that there are further parameters to take into account, like patient compliance. Is the patient ready to actually follow the treatment? There are so many things that a doctor has to do within the average few minutes he sees a patient that he needs support. He has to assess what his patient is more likely to do (take a pill, change his lifestyle, use a certain app), and then he should be able to see which one will be most beneficial for his patient.

Helene Schönewolf : These were my questions when I stopped working in pharma and started with Jacques the project RAMPmedical. We thought maybe doctors just need a drug list that is up-to-date. So we built a simple updated drug list with linked authorization information and some further product information from the relevant pharma company. And doctors found that suitable but clearly couldn’t use it to find the right treatment for any patient. And that’s when we understood how complex it is to make therapy decisions. So, in close cooperation with doctors we added more and more information and then we saw ourselves that this becomes a jungle of information.

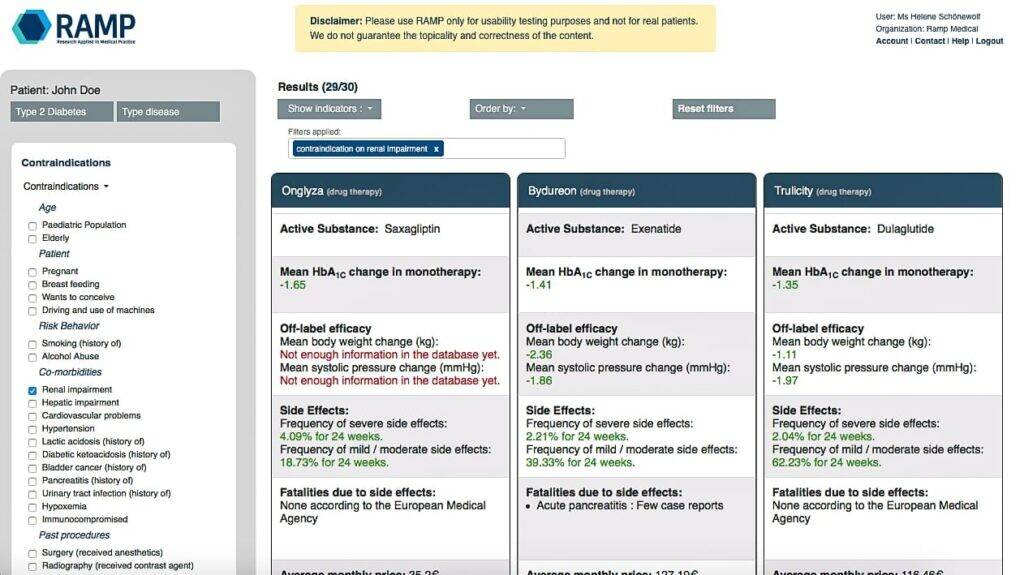

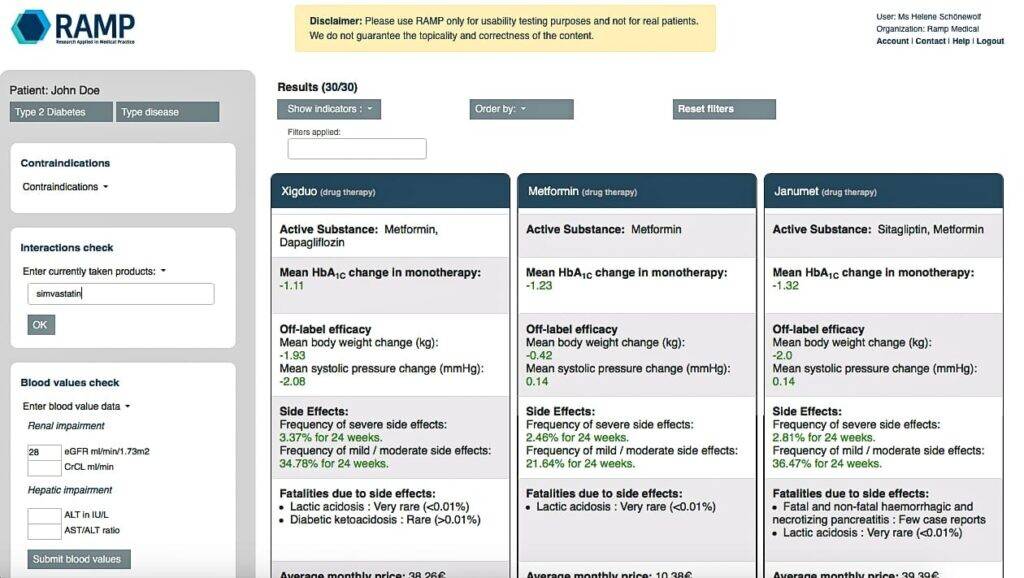

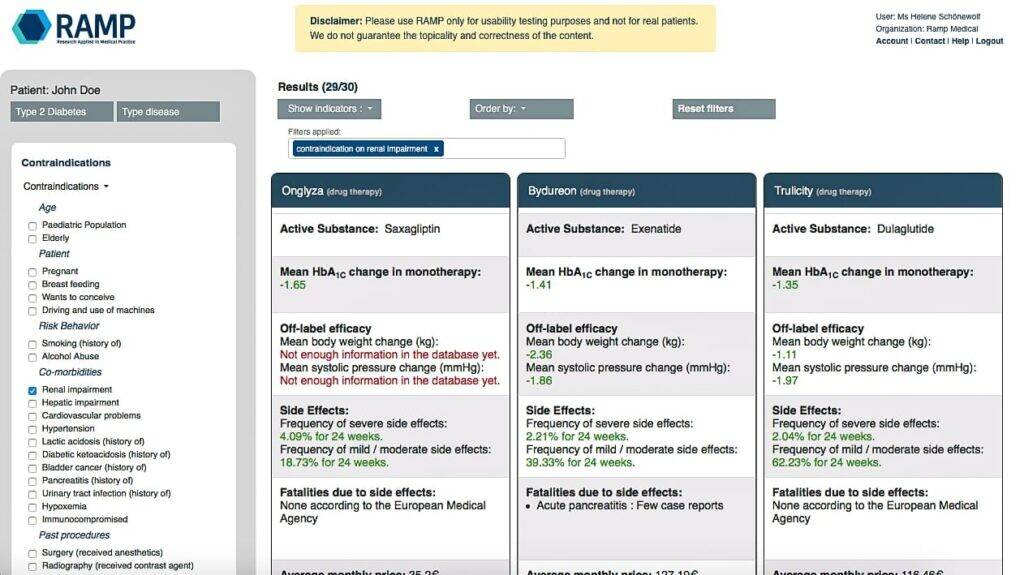

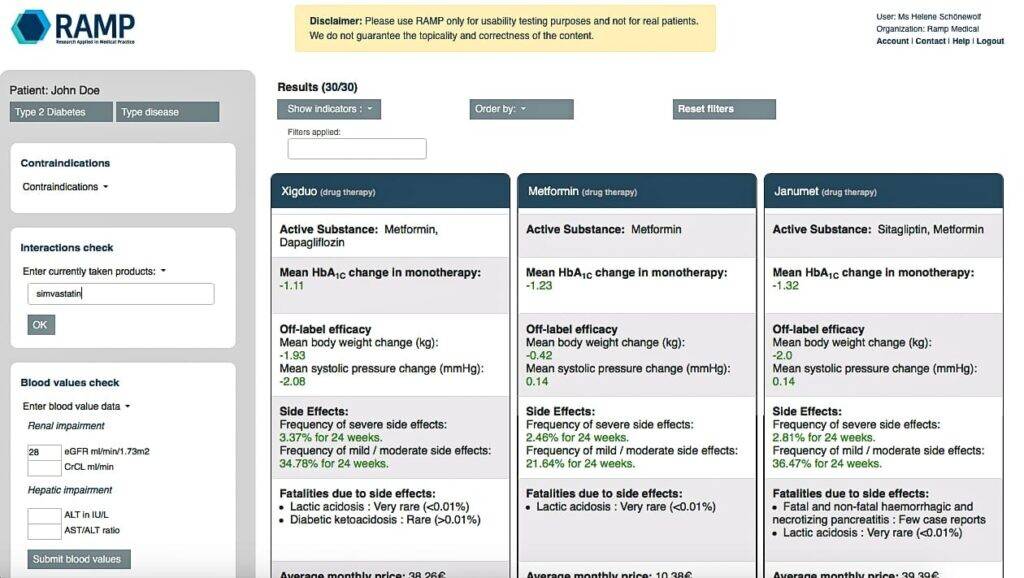

So, we began working on the structure of information, to make it rapidly usable. Because the doctor definitely needs to know many parameters of the treatment and the patient. That’s why when a patient goes to a doctor and tells him about a treatment that the patient read about on the internet and the doctor doesn’t prescribe it, it’s because the doctor needs to know more about the treatment. To make a therapy decision the doctor needs to know if the treatment is guideline coherent, if the treatment has been tested, if yes, with how many patients, how effective the treatment was, on what scale, how many side effects there were, for whom is it contraindicated, are there interactions with other drugs the patient is taking and much, much more information.

How can doctors be sure that the best "pill-case" match is the right one and that they can trust AI instead of trusting own intuition?

Helene Schönewolf :This is a very good point. Doctors and patients are for the most part uncomfortable about having a machine make the last call. That’s why we inform the doctor and rank the treatments. You still require a profound medical knowledge to be able to use RAMP. We don’t make the decision, we support the doctor making the decision.

Jacques Ehret: We keep everything transparent. How much evidence there is to support what we show, all the data used to show what we show, the sources themselves. We also show the risks of each therapy so he can be sure about how safe it is. We are also thinking about implementing a way to give him the possibility to know what another doctor would do in a similar case, but we are not there yet.

You've started to test your product in the field of diabetology first. What is your experience so far and which are the next fields of medicine to be involved in?

Helene Schönewolf : We are in the middle of our product trial, in the field of diabetology. The results are great so far. We knew what we were building and we were always in iteration with the doctors, but you never know if everything will turn out as expected. Jacques make a very good test design – randomized, with a “placebo” group, so without RAMP. With RAMP all doctors seem to avoid mistakes perfectly and identify the best treatment for every patient case. In the group without RAMP doctors make quite a lot of mistakes. The doctors are great it’s just very difficult to think of all of the contraindications and drug interactions. And nobody can remember all of these side effect ratios. That’s why it’s quite difficult to convince doctors to participate in the study. This doesn’t mean that doctors are badly trained, quite the contrary. This just shows how difficult therapy decisions are and how difficult it is to avoid mistakes.

Jacques Ehret: We have outstanding feedback. Our product significantly improves doctors’ decisions. All doctors who tried our product are amazed by how complete and clear it is, and are convinced that this will be really helpful in their daily work.

We are currently implementing pain therapy, and we will then add cardiology. After that we will add infectiology, oncology, pediatrics, neurology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, dermatology and ophthalmology. Our plan is to have all of this ready by next year.

The solution introduces AI into doctor's work. Do you think that we need a kind of change of mindset to convince doctors to use tools based on artificial intelligence? How to convince them that it's a help not a software tool that is competing with their competences?

Helene Schönewolf : I hear that it’s a common problem that doctors are afraid of being replaced by a computer but we rarely get this feedback. But this is maybe just regarding therapy decisions that are software supported. I think there is a big gap between therapy decision support and therapy decision making. When I discuss with doctors the tools that are actually required to make therapy decisions I don’t get from them the notion of being afraid about being replaced but about these tools being more work for the doctors. They calculate only one decision parameter with quite a low degree of accuracy and a big disclaimer is that the doctor is left alone to identify all other relevant decision parameters. And head doctors in hospitals should be relieved, because they can trust their employee doctors to do a better job and the experienced doctors can actually contribute by having their knowledge and experience influence therapy decisions through RAMP by publishing more publications that we represent in RAMP.

What is the most important factor now to speed up the research and development of RAMP?

Helene Schönewolf : We have 3 big tasks now. One is to expand the content to more medical fields and maintain quality. Second is to reinforce the technical infrastructure to support many users and to be completely safe. The third one is my task, to keep the project funded, to involve more partners like doctor’s associations and universities to contribute with know-how, and then to make sure that RAMP really gets to the patient.

Could you please describe your vision of doctor's work based on the principles of personalized- and evidence-based medicine?

Jacques Ehret: Well there are different milestones for this. First a doctor using our software to identify the best therapies there are for his patient based on the data the patient shared from his personal medical file. The second milestone in 15 years, a machine will pre-diagnose the patient, ask a medical professional to obtain more data if needed, refine the diagnosis. Once the patient sees the doctor, the machine will propose the 3 most likely diagnoses to the doctor, who will choose the proper diagnosis based on what he sees and obtains from the patient. Then, the machine, based on our software, will propose to the doctor the best 5 therapies for this particular patient, based on the data it had and the data it obtained. The doctor will then choose the therapy. The machine will then provide the prescription with the proper treatment in the correct dosage to the patient.

Helene Schönewolf : The doctor’s work will get more and more accurate and scientific, much less intuitive, thanks to technical innovation. This will also reinforce the change from a rigid social system in medicine to a transparent, high tech supported structure.

How can doctors be sure that the best "pill-case" match is the right one and that they can trust AI instead of trusting own intuition?

Helene Schönewolf :This is a very good point. Doctors and patients are for the most part uncomfortable about having a machine make the last call. That’s why we inform the doctor and rank the treatments. You still require a profound medical knowledge to be able to use RAMP. We don’t make the decision, we support the doctor making the decision.

Jacques Ehret: We keep everything transparent. How much evidence there is to support what we show, all the data used to show what we show, the sources themselves. We also show the risks of each therapy so he can be sure about how safe it is. We are also thinking about implementing a way to give him the possibility to know what another doctor would do in a similar case, but we are not there yet.

You've started to test your product in the field of diabetology first. What is your experience so far and which are the next fields of medicine to be involved in?

Helene Schönewolf : We are in the middle of our product trial, in the field of diabetology. The results are great so far. We knew what we were building and we were always in iteration with the doctors, but you never know if everything will turn out as expected. Jacques make a very good test design – randomized, with a “placebo” group, so without RAMP. With RAMP all doctors seem to avoid mistakes perfectly and identify the best treatment for every patient case. In the group without RAMP doctors make quite a lot of mistakes. The doctors are great it’s just very difficult to think of all of the contraindications and drug interactions. And nobody can remember all of these side effect ratios. That’s why it’s quite difficult to convince doctors to participate in the study. This doesn’t mean that doctors are badly trained, quite the contrary. This just shows how difficult therapy decisions are and how difficult it is to avoid mistakes.

Jacques Ehret: We have outstanding feedback. Our product significantly improves doctors’ decisions. All doctors who tried our product are amazed by how complete and clear it is, and are convinced that this will be really helpful in their daily work.

We are currently implementing pain therapy, and we will then add cardiology. After that we will add infectiology, oncology, pediatrics, neurology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, dermatology and ophthalmology. Our plan is to have all of this ready by next year.

The solution introduces AI into doctor's work. Do you think that we need a kind of change of mindset to convince doctors to use tools based on artificial intelligence? How to convince them that it's a help not a software tool that is competing with their competences?

Helene Schönewolf : I hear that it’s a common problem that doctors are afraid of being replaced by a computer but we rarely get this feedback. But this is maybe just regarding therapy decisions that are software supported. I think there is a big gap between therapy decision support and therapy decision making. When I discuss with doctors the tools that are actually required to make therapy decisions I don’t get from them the notion of being afraid about being replaced but about these tools being more work for the doctors. They calculate only one decision parameter with quite a low degree of accuracy and a big disclaimer is that the doctor is left alone to identify all other relevant decision parameters. And head doctors in hospitals should be relieved, because they can trust their employee doctors to do a better job and the experienced doctors can actually contribute by having their knowledge and experience influence therapy decisions through RAMP by publishing more publications that we represent in RAMP.

What is the most important factor now to speed up the research and development of RAMP?

Helene Schönewolf : We have 3 big tasks now. One is to expand the content to more medical fields and maintain quality. Second is to reinforce the technical infrastructure to support many users and to be completely safe. The third one is my task, to keep the project funded, to involve more partners like doctor’s associations and universities to contribute with know-how, and then to make sure that RAMP really gets to the patient.

Could you please describe your vision of doctor's work based on the principles of personalized- and evidence-based medicine?

Jacques Ehret: Well there are different milestones for this. First a doctor using our software to identify the best therapies there are for his patient based on the data the patient shared from his personal medical file. The second milestone in 15 years, a machine will pre-diagnose the patient, ask a medical professional to obtain more data if needed, refine the diagnosis. Once the patient sees the doctor, the machine will propose the 3 most likely diagnoses to the doctor, who will choose the proper diagnosis based on what he sees and obtains from the patient. Then, the machine, based on our software, will propose to the doctor the best 5 therapies for this particular patient, based on the data it had and the data it obtained. The doctor will then choose the therapy. The machine will then provide the prescription with the proper treatment in the correct dosage to the patient.

Helene Schönewolf : The doctor’s work will get more and more accurate and scientific, much less intuitive, thanks to technical innovation. This will also reinforce the change from a rigid social system in medicine to a transparent, high tech supported structure.

Jacques Ehret: It is hard to put both concepts into practice because both terms are to some extent antagonists: The stronger the evidence, the more the outcomes are generalizable to the global population. But since it is a statistical approach, the effect on specific patients may be really different from what is expected. The more personalized the medicine is, the less it may suit patients in general, and therefore insights into how safe a treatment is may be lost.

However, both can be put together because they involve different aspects of what a patient needs. In evidence-based medicine it is important to know how likely a treatment is to work on a patient, and what exactly the risks are for the individual patient, statistically speaking. This information can then be personalized for patients so they can choose between the safe treatments the ones that are more likely to work or will work well enough.

The biggest barrier to putting both concepts into practice is that it is hard to find the equilibrium between sufficient evidence and sufficient personalization. It is difficult because there are no rules for that but the combination of knowledge and experience. However, knowledge increases at a rate that no individual can follow. This is what we try to help the doctors with.

"One pill fits all" is today's medicine paradigm. On the other hand the pharmaceutical market is booming, the number of new medicines for the same diseases is growing quickly. Doctors can choose between thousands of drugs and from this point the problems begin: how to make the right decision? If the doctor's intuition is not enough, what could help?

Jacques Ehret: There are over 10.000 conditions according to the ICD-10 classification. New conditions are added yearly, either because they were not known, were misclassified, or even did not exist (new bacteria or virus for example). Some of these conditions have cures, some of them have treatments to alleviate the symptoms, and some of them do not have any relevant treatments.

There are more and more drugs on the market every year. Evidence about established drugs is increasing and therefore the extent of their safety is being updated constantly, sometimes to the point that they have to be withdrawn. Some conditions like cancer and diabetes get new treatments almost yearly. Some conditions are so rare that it is really difficult to design a treatment for them. Furthermore, pills are not the only treatment possibilities there are. Digital therapeutics, plants, lifestyle modifications, chemical exposure also impact many conditions. There are more than 300,000 "health" apps. Hundreds of plants, hundreds of different sports and diets.

We should not forget that science does not know everything about the human body yet. New discoveries lead to new potential targets for new treatments, and new mechanisms to understand so that the treatment is adequate for the patient. I believe that we still have a long way to go until we understand fully the whole human body, and until then we need to aggregate everything that we know about therapies, and adapt it as much as we can to each patient.

What is also difficult, is that there are further parameters to take into account, like patient compliance. Is the patient ready to actually follow the treatment? There are so many things that a doctor has to do within the average few minutes he sees a patient that he needs support. He has to assess what his patient is more likely to do (take a pill, change his lifestyle, use a certain app), and then he should be able to see which one will be most beneficial for his patient.

Helene Schönewolf : These were my questions when I stopped working in pharma and started with Jacques the project RAMPmedical. We thought maybe doctors just need a drug list that is up-to-date. So we built a simple updated drug list with linked authorization information and some further product information from the relevant pharma company. And doctors found that suitable but clearly couldn’t use it to find the right treatment for any patient. And that’s when we understood how complex it is to make therapy decisions. So, in close cooperation with doctors we added more and more information and then we saw ourselves that this becomes a jungle of information.

So, we began working on the structure of information, to make it rapidly usable. Because the doctor definitely needs to know many parameters of the treatment and the patient. That’s why when a patient goes to a doctor and tells him about a treatment that the patient read about on the internet and the doctor doesn’t prescribe it, it’s because the doctor needs to know more about the treatment. To make a therapy decision the doctor needs to know if the treatment is guideline coherent, if the treatment has been tested, if yes, with how many patients, how effective the treatment was, on what scale, how many side effects there were, for whom is it contraindicated, are there interactions with other drugs the patient is taking and much, much more information.

Jacques Ehret: It is hard to put both concepts into practice because both terms are to some extent antagonists: The stronger the evidence, the more the outcomes are generalizable to the global population. But since it is a statistical approach, the effect on specific patients may be really different from what is expected. The more personalized the medicine is, the less it may suit patients in general, and therefore insights into how safe a treatment is may be lost.

However, both can be put together because they involve different aspects of what a patient needs. In evidence-based medicine it is important to know how likely a treatment is to work on a patient, and what exactly the risks are for the individual patient, statistically speaking. This information can then be personalized for patients so they can choose between the safe treatments the ones that are more likely to work or will work well enough.

The biggest barrier to putting both concepts into practice is that it is hard to find the equilibrium between sufficient evidence and sufficient personalization. It is difficult because there are no rules for that but the combination of knowledge and experience. However, knowledge increases at a rate that no individual can follow. This is what we try to help the doctors with.

"One pill fits all" is today's medicine paradigm. On the other hand the pharmaceutical market is booming, the number of new medicines for the same diseases is growing quickly. Doctors can choose between thousands of drugs and from this point the problems begin: how to make the right decision? If the doctor's intuition is not enough, what could help?

Jacques Ehret: There are over 10.000 conditions according to the ICD-10 classification. New conditions are added yearly, either because they were not known, were misclassified, or even did not exist (new bacteria or virus for example). Some of these conditions have cures, some of them have treatments to alleviate the symptoms, and some of them do not have any relevant treatments.

There are more and more drugs on the market every year. Evidence about established drugs is increasing and therefore the extent of their safety is being updated constantly, sometimes to the point that they have to be withdrawn. Some conditions like cancer and diabetes get new treatments almost yearly. Some conditions are so rare that it is really difficult to design a treatment for them. Furthermore, pills are not the only treatment possibilities there are. Digital therapeutics, plants, lifestyle modifications, chemical exposure also impact many conditions. There are more than 300,000 "health" apps. Hundreds of plants, hundreds of different sports and diets.

We should not forget that science does not know everything about the human body yet. New discoveries lead to new potential targets for new treatments, and new mechanisms to understand so that the treatment is adequate for the patient. I believe that we still have a long way to go until we understand fully the whole human body, and until then we need to aggregate everything that we know about therapies, and adapt it as much as we can to each patient.

What is also difficult, is that there are further parameters to take into account, like patient compliance. Is the patient ready to actually follow the treatment? There are so many things that a doctor has to do within the average few minutes he sees a patient that he needs support. He has to assess what his patient is more likely to do (take a pill, change his lifestyle, use a certain app), and then he should be able to see which one will be most beneficial for his patient.

Helene Schönewolf : These were my questions when I stopped working in pharma and started with Jacques the project RAMPmedical. We thought maybe doctors just need a drug list that is up-to-date. So we built a simple updated drug list with linked authorization information and some further product information from the relevant pharma company. And doctors found that suitable but clearly couldn’t use it to find the right treatment for any patient. And that’s when we understood how complex it is to make therapy decisions. So, in close cooperation with doctors we added more and more information and then we saw ourselves that this becomes a jungle of information.

So, we began working on the structure of information, to make it rapidly usable. Because the doctor definitely needs to know many parameters of the treatment and the patient. That’s why when a patient goes to a doctor and tells him about a treatment that the patient read about on the internet and the doctor doesn’t prescribe it, it’s because the doctor needs to know more about the treatment. To make a therapy decision the doctor needs to know if the treatment is guideline coherent, if the treatment has been tested, if yes, with how many patients, how effective the treatment was, on what scale, how many side effects there were, for whom is it contraindicated, are there interactions with other drugs the patient is taking and much, much more information.

Our mission is to fix a bottleneck in the healthcare system by providing doctors an easy to use knowledge and decision making toolThe challenge is not just to oversee the details but to remember all of this. And for all of the therapies available, this is simply impossible. That’s why doctors only very slowly change their prescription habits. Existing software solutions list either the sources, like guidelines, product information, there are few publications but the doctor still has to read them and memorize it all or real decision software tries to calculate effectiveness values, but as I already mentioned, these are not the only values the doctor needs. So at RAMPmedical we try to include all treatment and decision characteristics, match them with patient particularities and in so doing identify the best and safest treatment for the patient. At the moment our diabetology beta version is being tested and with RAMPmedical doctors seem to identify within 1 minute on average for each patient the best and safest treatment. So no more overlooked contraindications or drug interactions and no unnecessarily high side effects. This also relieves a lot of pressure on the doctors, even if they are still complaining about the UX. But we’re working on that and hope to get more funding soon to expand into more medical fields - pain medicine is half complete. How did you hit on this idea to develop an online platform that could help doctors to make evidence-based decisions? And what motivates you to bring this idea to the market? Helene Schönewolf : Jacques worked in medical research and I worked in pharma marketing. We saw how big the difference was between what Jacques in medical research had already discovered and what I in pharma marketing brought to doctors. There were 20 – 30 years between the two. Even for new really innovative drugs it takes many years until every patient gets to benefit from the drug. And you really can’t say that pharma spends too little money to bring their products to market. However, if someone close to me gets really sick, I want them to get the best possible treatment. And I don’t accept that someone close to me may suffer or die for want of a simple solution. The problem is just that scientific information is too complicated and takes too much time to read. At the same time, I’m from a family of doctors and also see that doctors suffer from this. That is what drives me. Jacques Ehret: We saw the difference in the content between conferences for scientists and conferences for medical doctors and understood that there is a huge gap there. We also saw that doctors do not have a lot of time, and that the information that was brought to them was not always neutral nor transparent. The result is that patients are treated suboptimally, compared to what they could receive. The only way to solve this problem in our eyes was to make an online platform to bring them all the information that there is about therapeutics, adapted as much as possible to the patient, showing all of the parameters relevant to a decision in an easily comparable way, so that doctors can easily find the right therapy without perturbing their workday. We are motivated whenever we hear that someone is receiving a therapy that he should not have received. Or whenever someone is not receiving a therapy that exists but their doctor is not aware of it. Or whenever we hear doctors say how impressed they are by our platform and how much it will help them once it includes all of the therapies relevant to their specialty. Could you please describe step by step how RAMP is build and how it works? Jacques Ehret: We use many different types of sources. Guidelines from doctors associations to establish what are the best practices in a country and all around the world. Product characteristics published by the regulatory authorities to inform the reader about drug behaviour (contraindications, interactions, side-effects, posology, special populations). Those data might be completed by scientific articles. Clinical trials to know how much a therapy works, on which outcomes (whether a diabetes drug also helps with blood pressure and lipidemia and how much for example), how safe they are, and on whom. We have scientists that extract all of this data by hand, but they are assisted by scripts that partly-automatize their work. Scripts can be used to search for whether there have been updates in the sources, and to highlight the relevant parts in a publication, and extract data. All those data are put together into a really complex database, and then aggregated to show to the doctors what is relevant, and not 10 different values about how one substance improves diabetes. For the doctor himself, he has to enter the relevant patient data (but we are working to automatize this part). Then the software shows what therapies are adequate for his patient. He can then sort them by efficacy, safety, strength of the evidence, and more. Then he just has to choose according to what he sees and what he knows. He also has the possibility to dig deeper to view more data about the therapy, but also where the data comes from if he is ever in any doubt about what is shown.

How can doctors be sure that the best "pill-case" match is the right one and that they can trust AI instead of trusting own intuition?

Helene Schönewolf :This is a very good point. Doctors and patients are for the most part uncomfortable about having a machine make the last call. That’s why we inform the doctor and rank the treatments. You still require a profound medical knowledge to be able to use RAMP. We don’t make the decision, we support the doctor making the decision.

Jacques Ehret: We keep everything transparent. How much evidence there is to support what we show, all the data used to show what we show, the sources themselves. We also show the risks of each therapy so he can be sure about how safe it is. We are also thinking about implementing a way to give him the possibility to know what another doctor would do in a similar case, but we are not there yet.

You've started to test your product in the field of diabetology first. What is your experience so far and which are the next fields of medicine to be involved in?

Helene Schönewolf : We are in the middle of our product trial, in the field of diabetology. The results are great so far. We knew what we were building and we were always in iteration with the doctors, but you never know if everything will turn out as expected. Jacques make a very good test design – randomized, with a “placebo” group, so without RAMP. With RAMP all doctors seem to avoid mistakes perfectly and identify the best treatment for every patient case. In the group without RAMP doctors make quite a lot of mistakes. The doctors are great it’s just very difficult to think of all of the contraindications and drug interactions. And nobody can remember all of these side effect ratios. That’s why it’s quite difficult to convince doctors to participate in the study. This doesn’t mean that doctors are badly trained, quite the contrary. This just shows how difficult therapy decisions are and how difficult it is to avoid mistakes.

Jacques Ehret: We have outstanding feedback. Our product significantly improves doctors’ decisions. All doctors who tried our product are amazed by how complete and clear it is, and are convinced that this will be really helpful in their daily work.

We are currently implementing pain therapy, and we will then add cardiology. After that we will add infectiology, oncology, pediatrics, neurology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, dermatology and ophthalmology. Our plan is to have all of this ready by next year.

The solution introduces AI into doctor's work. Do you think that we need a kind of change of mindset to convince doctors to use tools based on artificial intelligence? How to convince them that it's a help not a software tool that is competing with their competences?

Helene Schönewolf : I hear that it’s a common problem that doctors are afraid of being replaced by a computer but we rarely get this feedback. But this is maybe just regarding therapy decisions that are software supported. I think there is a big gap between therapy decision support and therapy decision making. When I discuss with doctors the tools that are actually required to make therapy decisions I don’t get from them the notion of being afraid about being replaced but about these tools being more work for the doctors. They calculate only one decision parameter with quite a low degree of accuracy and a big disclaimer is that the doctor is left alone to identify all other relevant decision parameters. And head doctors in hospitals should be relieved, because they can trust their employee doctors to do a better job and the experienced doctors can actually contribute by having their knowledge and experience influence therapy decisions through RAMP by publishing more publications that we represent in RAMP.

What is the most important factor now to speed up the research and development of RAMP?

Helene Schönewolf : We have 3 big tasks now. One is to expand the content to more medical fields and maintain quality. Second is to reinforce the technical infrastructure to support many users and to be completely safe. The third one is my task, to keep the project funded, to involve more partners like doctor’s associations and universities to contribute with know-how, and then to make sure that RAMP really gets to the patient.

Could you please describe your vision of doctor's work based on the principles of personalized- and evidence-based medicine?

Jacques Ehret: Well there are different milestones for this. First a doctor using our software to identify the best therapies there are for his patient based on the data the patient shared from his personal medical file. The second milestone in 15 years, a machine will pre-diagnose the patient, ask a medical professional to obtain more data if needed, refine the diagnosis. Once the patient sees the doctor, the machine will propose the 3 most likely diagnoses to the doctor, who will choose the proper diagnosis based on what he sees and obtains from the patient. Then, the machine, based on our software, will propose to the doctor the best 5 therapies for this particular patient, based on the data it had and the data it obtained. The doctor will then choose the therapy. The machine will then provide the prescription with the proper treatment in the correct dosage to the patient.

Helene Schönewolf : The doctor’s work will get more and more accurate and scientific, much less intuitive, thanks to technical innovation. This will also reinforce the change from a rigid social system in medicine to a transparent, high tech supported structure.

How can doctors be sure that the best "pill-case" match is the right one and that they can trust AI instead of trusting own intuition?

Helene Schönewolf :This is a very good point. Doctors and patients are for the most part uncomfortable about having a machine make the last call. That’s why we inform the doctor and rank the treatments. You still require a profound medical knowledge to be able to use RAMP. We don’t make the decision, we support the doctor making the decision.

Jacques Ehret: We keep everything transparent. How much evidence there is to support what we show, all the data used to show what we show, the sources themselves. We also show the risks of each therapy so he can be sure about how safe it is. We are also thinking about implementing a way to give him the possibility to know what another doctor would do in a similar case, but we are not there yet.

You've started to test your product in the field of diabetology first. What is your experience so far and which are the next fields of medicine to be involved in?

Helene Schönewolf : We are in the middle of our product trial, in the field of diabetology. The results are great so far. We knew what we were building and we were always in iteration with the doctors, but you never know if everything will turn out as expected. Jacques make a very good test design – randomized, with a “placebo” group, so without RAMP. With RAMP all doctors seem to avoid mistakes perfectly and identify the best treatment for every patient case. In the group without RAMP doctors make quite a lot of mistakes. The doctors are great it’s just very difficult to think of all of the contraindications and drug interactions. And nobody can remember all of these side effect ratios. That’s why it’s quite difficult to convince doctors to participate in the study. This doesn’t mean that doctors are badly trained, quite the contrary. This just shows how difficult therapy decisions are and how difficult it is to avoid mistakes.

Jacques Ehret: We have outstanding feedback. Our product significantly improves doctors’ decisions. All doctors who tried our product are amazed by how complete and clear it is, and are convinced that this will be really helpful in their daily work.

We are currently implementing pain therapy, and we will then add cardiology. After that we will add infectiology, oncology, pediatrics, neurology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, dermatology and ophthalmology. Our plan is to have all of this ready by next year.

The solution introduces AI into doctor's work. Do you think that we need a kind of change of mindset to convince doctors to use tools based on artificial intelligence? How to convince them that it's a help not a software tool that is competing with their competences?

Helene Schönewolf : I hear that it’s a common problem that doctors are afraid of being replaced by a computer but we rarely get this feedback. But this is maybe just regarding therapy decisions that are software supported. I think there is a big gap between therapy decision support and therapy decision making. When I discuss with doctors the tools that are actually required to make therapy decisions I don’t get from them the notion of being afraid about being replaced but about these tools being more work for the doctors. They calculate only one decision parameter with quite a low degree of accuracy and a big disclaimer is that the doctor is left alone to identify all other relevant decision parameters. And head doctors in hospitals should be relieved, because they can trust their employee doctors to do a better job and the experienced doctors can actually contribute by having their knowledge and experience influence therapy decisions through RAMP by publishing more publications that we represent in RAMP.

What is the most important factor now to speed up the research and development of RAMP?

Helene Schönewolf : We have 3 big tasks now. One is to expand the content to more medical fields and maintain quality. Second is to reinforce the technical infrastructure to support many users and to be completely safe. The third one is my task, to keep the project funded, to involve more partners like doctor’s associations and universities to contribute with know-how, and then to make sure that RAMP really gets to the patient.

Could you please describe your vision of doctor's work based on the principles of personalized- and evidence-based medicine?

Jacques Ehret: Well there are different milestones for this. First a doctor using our software to identify the best therapies there are for his patient based on the data the patient shared from his personal medical file. The second milestone in 15 years, a machine will pre-diagnose the patient, ask a medical professional to obtain more data if needed, refine the diagnosis. Once the patient sees the doctor, the machine will propose the 3 most likely diagnoses to the doctor, who will choose the proper diagnosis based on what he sees and obtains from the patient. Then, the machine, based on our software, will propose to the doctor the best 5 therapies for this particular patient, based on the data it had and the data it obtained. The doctor will then choose the therapy. The machine will then provide the prescription with the proper treatment in the correct dosage to the patient.

Helene Schönewolf : The doctor’s work will get more and more accurate and scientific, much less intuitive, thanks to technical innovation. This will also reinforce the change from a rigid social system in medicine to a transparent, high tech supported structure.