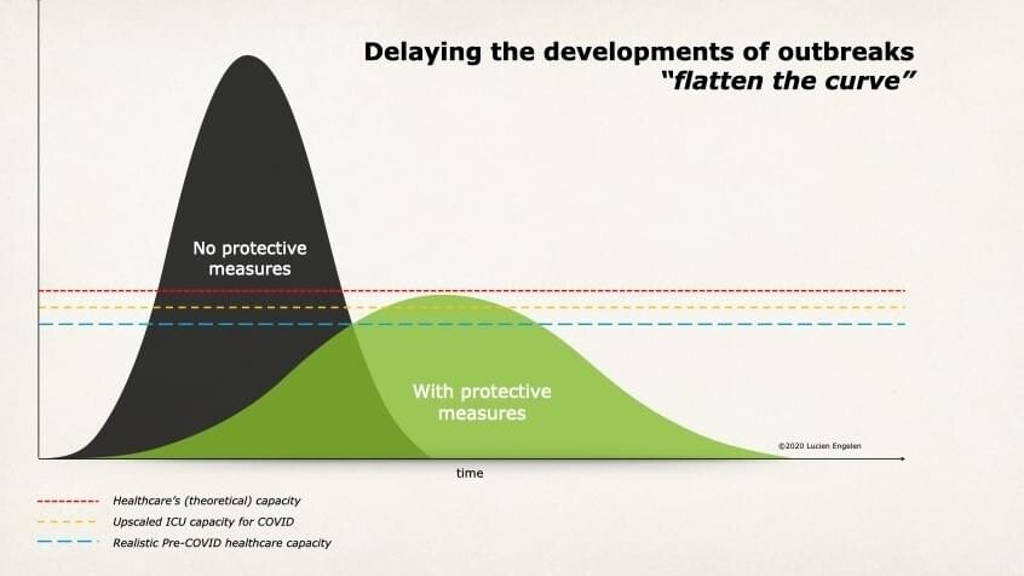

But what if this positive difference actually leads to an unintended yet misleading distraction? And what if, by only focusing on flattening the curve, we are losing sight of what’s happening beyond it: the curves to come?

I believe the typical curve represents a skewed reality, assuming as it does that interventions are capable of preventing the healthcare system from breaching its maximum capacity. But to me, the line representing ‘healthcare capacity’ is the misleading part. Because while it is true for ICU-capacity – for which these graphs are often applied - it suggests these measures also impact total capacity.

The true picture is that capacity was actually under severe pressure in normal circumstances before COVID19 struck the world. With the burden of administration representing 40% of the system’s workload, precious resources are being drawn away from the real work of treating patients. Costs are surging, demand doubling, and skills in short supply. And so, if the system was strained before the outbreak, how much more so will it be during it – whatever measures we take?

The idea that we can remain within the limits of healthcare capacity just doesn’t seem realistic during such a cataclysmic event as the COVID-19 pandemic

Yet even as we underestimate the demands of this current phase, a new storm is building in the background. And ‘flattening the curve’, which is the right approach for this first attack of COVID-19, is hiding it - and the crucial next challenges that follow - from view. By plotting the management of coronavirus against healthcare capacity, these graphs only address the issue in 2D. We should, however, be looking at the situation in 3D. And a 3D graph would show us what is waiting to crash down on an as yet unsuspecting health ecosystem. From that perspective, multiple peaks and multiple challenges await.

A perfect storm of postponed treatments, regular cold, seasonal flu and a possible next wave two COVID

So what are the conditions leading to this build-up? Well, we needed to take aggressive measures to flatten the curve, which has resulted in the postponement of regular routine procedures and treatments. From a 2D viewpoint, this helps to free up capacity, alleviating pressure on the system, and keeping us below this imaginary line (which was, in any case, a speculative addition to the graph).

Yet in actual fact, all we are doing is delaying and even worsening non-coronavirus issues, not avoiding them. Postponing treatment means allowing conditions to deteriorate to more severe stages. One can only put certain procedures or operations on hold for so long. The same goes for mental care, with a lack of treatment exacerbated by the effects of lockdown.

For the sake of argument

Let’s hypothesize the curve flattens and eases away around mid-June. It starts to look as if we have come out of the other side. But there will be no calm before the storm and we urgently need to understand this fact. Graphs tend to suggest a time for rest and recuperation once the peak subsides, but in my opinion, this will not be the case.

By early September, the challenge of catching up on stalled regular interventions will be compounded by a return of catching a cold, the seasonal flu, not to mention the expected second wave of COVID-19. When the immune systems of much of our population have been severely bombarded by a coronavirus, this alone could be enough to overwhelm healthcare provision – and yet this is only one side of the story.

At some point, we will have to pay the human cost of months of intense and stressful duty on the front line of the fight against coronavirus

Right now, we are seeing health workers pushing the limits in long 12, 14, even 16-hour shifts – all too often without even taking a break. Simply donning and enduring layer after layer of protective clothing, masks, and visors is a strain in itself. Beyond the physical effects of such intense and prolonged working conditions, there are also mental stresses. The distressing mortality rates. Deciding who will live and who cannot. It takes a toll.

This is all quite unsustainable of course. Our health workers are running on sheer adrenaline. But we have learned from former crises, whether earthquakes or warfare, that when the adrenaline ceases to flow, people start to collapse.

We also need to remember that a good number of staff have been reallocated to ICU-support. Once all these delayed treatments come back into play, they will be badly needed in their usual roles. At the same time, there will still be a demand for additional ICU staff to deal with both COVID-19 and regular ICU-care. Who fills the gap?

Once the pandemic dies down, we could see absenteeism hit rates of 25 to 35 percent over the months that follow. Health workers sick not from coronavirus, but from the exhaustion of being on the front-line for weeks. PTSS will certainly have to be factored into the mix as well, never mind the well-earned leave accrued.

This makes a mockery of any straight line implying a constant, unchanging capacity. Not to mention the act that healthcare capacity is never constant anyway. After all, we might start off with available personnel, supplies, facilities, and infrastructure to support current standards of care.

Yet as the system becomes overwhelmed, personnel become tired and less reliable, large numbers of infected people enter the system, and a backlog of routine treatments builds up, logistical and supply-demand will come under pressure. Capacity is clearly going to be affected.

We are standing at the edge. Acting now will not be a day too soon

It is with great pride and gratitude I look at what has been achieved and how the world, in general, has reacted - specifically our front-line healthcare professionals, supporting departments, and also most governments who have all been following the same cause and principles based on science.

But now the next phase is now knocking at our door. Look beyond the curve and we see a looming tower of issues waiting to crash down on an already exhausted health system - and ‘flatten the curve’ graphs simply do not account for it. And by the way, this also poses another danger: the likelihood of lulling people into a false sense of security. An ‘it’ll be all right in the end’ mindset risks a dangerous underestimation of the seriousness of the situation not only among the general population but also among leadership.

The good news is that healthcare professionals are aware of this build-up behind the scenes. Conversations are beginning to take place. Pockets of discussion are starting to ignite.

It is time to think not in terms of a flattening the curve, but the curves

That will take a holistic approach that integrates capacity management, health expertise, and logistical frameworks – both from outside the healthcare system as well as from the inside, as existing capacity will not be sufficient. Yet it is within our grasp and I’ve been heartened to see an overwhelming number of offers of support from companies like Deloitte, all prepared to come in and create an ‘impact that matters’ in this non-commercial setting.

To avoid a near future cycle of lockdown-release-lockdown-release, we need a transition strategy that puts us in control of the virus. We need to think not just in terms of flattening the curve, but in getting ahead of it - and preparing for the next one and the one after that.

In my next article, I’ll emphasize the aspects of an intervention strategy to flatten the curveS.