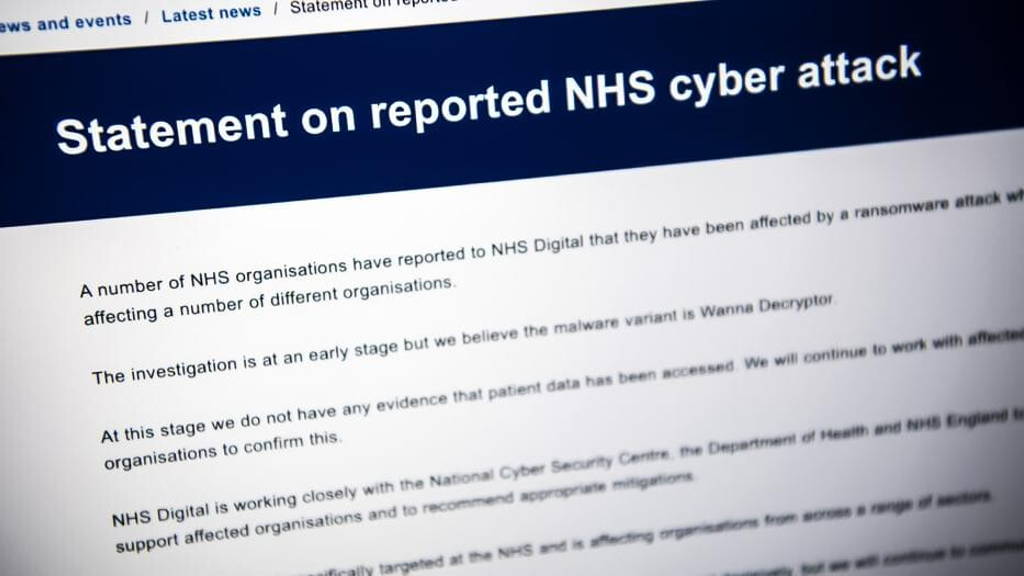

The attack started Friday May 12th in the UK, when sixteen hospitals had to suspend operations and divert patients because computers were encrypted, preventing access to vital information. At least 61 NHS organisations were compromised by the attack. 300 bitcoins was the going rate for decrypting a pc and regaining access. The infection spread rapidly en went global, using a combination of ransomware and a so called worm that spread from infected computers to exploit other vulnerability’s in computer systems.

The impact was big for both healthcare workers and patients. General practitioners were also hit, with many of them working on updating the vulnerability in systems that were attacked by WannaCry. People were adviced to postpone regular visits.

Dr Anne Rainsberry, National Incident Director, believes there are encouraging signs that the situation is improving, with fewer hospitals having to divert patients from their A&E units. "The message to patients is clear: the NHS is open for business. Staff are working hard to ensure that the small number of organisations still affected return to normal shortly. If people have hospital or GP appointments they should attend unless told otherwise. The latest information can be found on the NHS Choices website."

On Saturday a United Kingdom-based researcher discovered a way to slow down the spread of the ransomware strain that caused massive disruption to the U.K. healthcare system. The killswitch that was then posted, does not help computers already infected, but prevents further infection. Theories abound as to the origins and the reasons behind the attack, from pure criminals wanting to make big money to a state sponsored attack. Security firms Kaspersky and Symantec say the code used in WannaCry resembles code used by the lazarus Group, that might be based in North Korea.

Another explanation is that to many NHS organisations didn't install the patch Microsoft provided last March, to deal with a vulnerability in something called Server Message Block, which is a protocol for sharing files across a network. To update takes time when many computer systems are a patchwork themselves. A third explanation might be that since the collapse of the disastrous NHS National Programme for IT there is no longer a centralised approach to things like updates - each trust goes its own way. Some are ahead of the game, others are slower to respond, looking at money as a problem.

The impact was big for both healthcare workers and patients. General practitioners were also hit, with many of them working on updating the vulnerability in systems that were attacked by WannaCry. People were adviced to postpone regular visits.

2 Hospitals still ‘on divert’

According to an NHS update, as of 3pm on Monday, two hospitals remain on divert following the ransomware cyber-attack, down from seven on Sunday. NHS England says it is continuing to work with GP surgeries to ensure that they are putting in place a range of measures to protect themselves.Dr Anne Rainsberry, National Incident Director, believes there are encouraging signs that the situation is improving, with fewer hospitals having to divert patients from their A&E units. "The message to patients is clear: the NHS is open for business. Staff are working hard to ensure that the small number of organisations still affected return to normal shortly. If people have hospital or GP appointments they should attend unless told otherwise. The latest information can be found on the NHS Choices website."

Lack of updates

WannaCry exploited a vulnerability in Windows operating software.The vulnerability was discovered by the National Security Agency and leaked by a group called the Shadow Brokers. In March, Microsoft released a patch for fixing the vulnerability. But not every organization had updated its software since then.On Saturday a United Kingdom-based researcher discovered a way to slow down the spread of the ransomware strain that caused massive disruption to the U.K. healthcare system. The killswitch that was then posted, does not help computers already infected, but prevents further infection. Theories abound as to the origins and the reasons behind the attack, from pure criminals wanting to make big money to a state sponsored attack. Security firms Kaspersky and Symantec say the code used in WannaCry resembles code used by the lazarus Group, that might be based in North Korea.

Vulnerability UK hospitals

What made the UK hospitals so vulnerable, is a question the BBC askes. There are plenty of theories - like the fact that that far too many computers in hospitals were running Windows XP. Microsoft stopped support for this OS in 2014, leaving it vulnerable to attacks. Microsoft did release an emercency patch to deal with the Wannacry threat. The government warned NHS trusts in 2014 that they needed to move away from XP as rapidly as possible, but the warning wasn't headed very often. At the end of last year the software firm Citrix said that a Freedom of Information request had revealed that 90% of hospitals still had machines running on Windows XP.Another explanation is that to many NHS organisations didn't install the patch Microsoft provided last March, to deal with a vulnerability in something called Server Message Block, which is a protocol for sharing files across a network. To update takes time when many computer systems are a patchwork themselves. A third explanation might be that since the collapse of the disastrous NHS National Programme for IT there is no longer a centralised approach to things like updates - each trust goes its own way. Some are ahead of the game, others are slower to respond, looking at money as a problem.