Ingestible sensors could help doctors diagnose gastrointestinal disorders that slow down the passage of food through the digestive tract. They could also be used to detect food pressing on the stomach, helping doctors to monitor food intake by patients being treated for obesity. The flexible devices used, are based on piezoelectric materials, which generate a current and voltage when they are mechanically deformed. They also incorporate polymers with elasticity similar to that of human skin, so that they can conform to the skin and stretch when the skin stretches.

“Having flexibility has the potential to impart significantly improved safety, simply because it makes it easier to transit through the GI tract,” explains Giovanni Traverso, research affiliate at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, a gastroenterologist and biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and one of the senior authors of the paper.

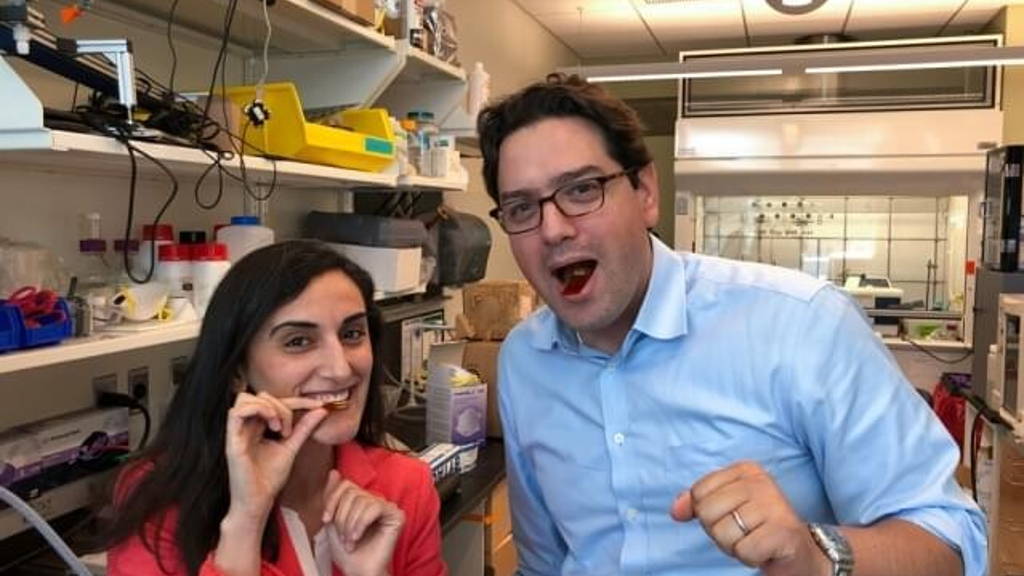

Canan Dagdeviren, an assistant professor in MIT’s Media Lab and the director of the Conformable Decoders research group, is the paper’s lead author and one of the corresponding authors. Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor and a member of the Koch Institute, is also an author of the paper.

Previously developed ingestible electronics typically use batteries that contain materials that, if leaked, are toxic to the human body. Other techniques, such as harvesting heat or vibrations from the surroundings, have been attempted. Most of these methods don’t produce enough consistent energy to power the sensors in the devices. The type of power the MIT/Womens Hospital team published about last february, could offer a safer and lower-cost alternative to the traditional batteries now used to power such devices.

With the goal of developing a more flexible sensor that might offer improved safety, Traverso teamed up with Dagdeviren, who previously developed flexible electronic devices such as a wearable blood pressure sensor and flexible mechanical energy harvesters.

In tests in pigs, the sensors successfully adhered to the stomach lining after being delivered endoscopically. Through external cables, the sensors transmitted information about how much voltage the piezoelectrical sensor generated, from which the researchers could calculate how much the stomach wall was moving, as well as distinguish when food or liquid were ingested.

Doctors could also use it to help measure the food intake of patients being treated for obesity. “Having a window into what an individual is actually ingesting at home is helpful, because sometimes it’s difficult for patients to really benchmark themselves and know how much is being consumed,” Traverso says.

In future versions of the device, the researchers plan to harvest some of the energy generated by the piezoelectric material to power other features, including additional sensors and wireless transmitters. Such devices would not require a battery, further improving their potential safety.

The tiny origami can unfold itself from a swallowed capsule (that disolves in stomach acid) and, steered by external magnetic fields, crawl across the stomach wall to remove a swallowed button battery or patch a wound. This was shown in experiments involving a simulation of the human esophagus and stomach.

Active for up to two days

In a study in the Oct. 10 issue of Nature Biomedical Engineering, the researchers demonstrated that the sensor remains active in the stomachs of pigs for up to two days. The flexibility of the device could offer improved safety over more rigid ingestible devices, the researchers say.“Having flexibility has the potential to impart significantly improved safety, simply because it makes it easier to transit through the GI tract,” explains Giovanni Traverso, research affiliate at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, a gastroenterologist and biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and one of the senior authors of the paper.

Canan Dagdeviren, an assistant professor in MIT’s Media Lab and the director of the Conformable Decoders research group, is the paper’s lead author and one of the corresponding authors. Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor and a member of the Koch Institute, is also an author of the paper.

Other ingestible electronics

Earlier this year Traverso and Langer were part of another science team looking into ingestible electronics. That team from MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, designed and demonstrated a small voltaic cell that is sustained by the acidic fluids in the stomach. The system can generate enough power to run small sensors or drug delivery devices that can reside in the gastrointestinal tract for extended periods of time.Previously developed ingestible electronics typically use batteries that contain materials that, if leaked, are toxic to the human body. Other techniques, such as harvesting heat or vibrations from the surroundings, have been attempted. Most of these methods don’t produce enough consistent energy to power the sensors in the devices. The type of power the MIT/Womens Hospital team published about last february, could offer a safer and lower-cost alternative to the traditional batteries now used to power such devices.

With the goal of developing a more flexible sensor that might offer improved safety, Traverso teamed up with Dagdeviren, who previously developed flexible electronic devices such as a wearable blood pressure sensor and flexible mechanical energy harvesters.

Capsule dissolves after swallowing

To make the new sensor, Dagdeviren first fabricates electronic circuits on a silicon wafer. The circuits contain two electrodes: a gold electrode placed atop a piezoelectric material called PZT, and a platinum electrode on the underside of the PZT. The ingestible sensor that the researchers designed for this study is 2 by 2.5 centimeters and can be rolled up and placed in a capsule that dissolves after being swallowed.In tests in pigs, the sensors successfully adhered to the stomach lining after being delivered endoscopically. Through external cables, the sensors transmitted information about how much voltage the piezoelectrical sensor generated, from which the researchers could calculate how much the stomach wall was moving, as well as distinguish when food or liquid were ingested.

Monitoring motility

This type of sensor could make it easier to diagnose digestive disorders that impair motility of the digestive tract, which can result in difficulty swallowing, nausea, gas, or constipation.Doctors could also use it to help measure the food intake of patients being treated for obesity. “Having a window into what an individual is actually ingesting at home is helpful, because sometimes it’s difficult for patients to really benchmark themselves and know how much is being consumed,” Traverso says.

In future versions of the device, the researchers plan to harvest some of the energy generated by the piezoelectric material to power other features, including additional sensors and wireless transmitters. Such devices would not require a battery, further improving their potential safety.

Ingestible origami robot

Another ingestible medical device was developed back in 2016, also with MIT help. The ingestible origami robot that can remove objects that have been accidentaly swallowed, wasbeen developed by a team of scientists at MIT, the University of Sheffield, and the Tokyo Institute of Technology.The tiny origami can unfold itself from a swallowed capsule (that disolves in stomach acid) and, steered by external magnetic fields, crawl across the stomach wall to remove a swallowed button battery or patch a wound. This was shown in experiments involving a simulation of the human esophagus and stomach.