Ultrasound as a diagnostic method has been around for a long time. Its application as a form of therapy treatment is relatively new. In this process, ultrasound waves are highly concentrated to destroy diseased tissue, tumor cells in particular, and render them harmless. Focused ultrasound benefits patients in several ways. The therapy is completely non-invasive and can be performed without anesthesia, and there are no operation wounds.

Until now, however, the method has only been approved for a limited number of indications, such as treatment of prostate cancer, bone metastases, and uterine myoma. To treat organs that move when patients breathe, the method can only be partially applied. Doctors have to rely on patients to hold their breath or put them under anesthesia, so they can control the patient’s breath.

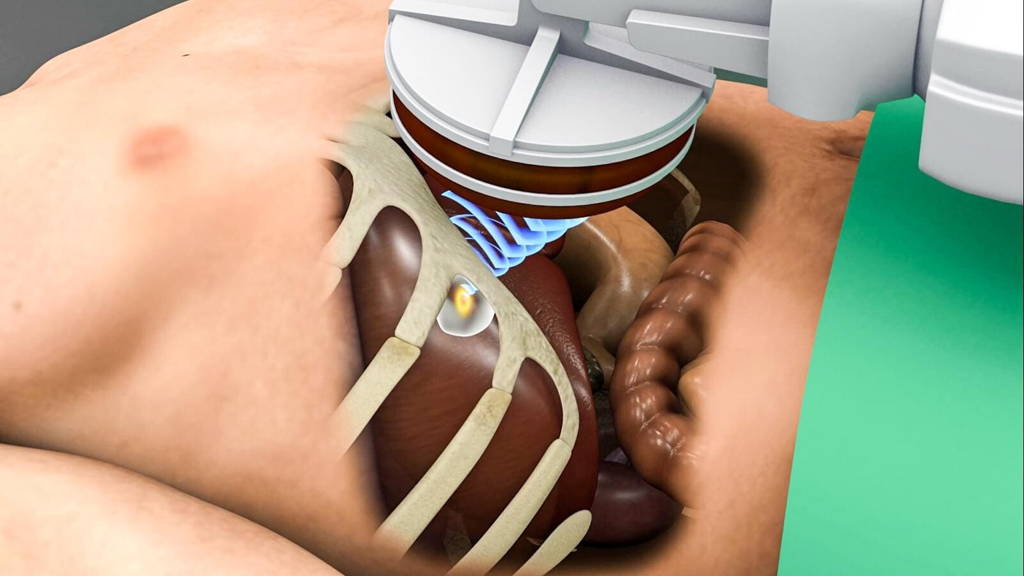

In the new therapy concept, the patient lies in an MRI scanner during the procedure. Every tenth of a second, the scanner produces an image showing the current position of the liver. The ultrasound transducer, a device equipped with more than 1000 small ultrasound transmitters, sits on the patient’s stomach. These can be directed so that their waves converge precisely at a point as small as a grain of rice. There, they unleash their destructive effect - the tumor cells become completely cooked. The MRI scanner controls the process, measuring the temperature in the liver and ensuring that the correct spots are sufficiently heated.

The program determines the path for the focused ultrasound waves to reach the liver tumor even when the patient moves while breathing. Developing the software was quite challenging: it must run both highly realiably and in real time.

Another difficulty facing the scientists was the fact that the ribs lie in front of the liver. To prevent the beams from damaging the ribs, elements in the ultrasound transducer that would have hit the ribs were deactivated, much like blocking the holes in a showerhead which spray water in an unwanted direction.

The first TRANS-FUSIMO tests on patients are planned for mid-2018. Thereafter, in cooperation with an industry partner, medical product certification can be tackled. If the method proves itself, in the future, it would be possible to treat other organs that move with breathing, such as the kidney, pancreas, or even lungs.

Until now, however, the method has only been approved for a limited number of indications, such as treatment of prostate cancer, bone metastases, and uterine myoma. To treat organs that move when patients breathe, the method can only be partially applied. Doctors have to rely on patients to hold their breath or put them under anesthesia, so they can control the patient’s breath.

Another path

The scientists working in the TRANS-FUSIMO EU project, coordinated by the Fraunhofer Institute for Medical Image Computing MEVIS in Bremen, are following another path. They refocus the ultrasound beam to the movement of the liver to reach the tumor effectively while sparing the surrounding healthy tissue. The fundamental technology needed for the method is now ready. The researchers will present important preliminary results as part of an industry symposium at the European Radiology Congress (ECR) in Vienna on March 1.In the new therapy concept, the patient lies in an MRI scanner during the procedure. Every tenth of a second, the scanner produces an image showing the current position of the liver. The ultrasound transducer, a device equipped with more than 1000 small ultrasound transmitters, sits on the patient’s stomach. These can be directed so that their waves converge precisely at a point as small as a grain of rice. There, they unleash their destructive effect - the tumor cells become completely cooked. The MRI scanner controls the process, measuring the temperature in the liver and ensuring that the correct spots are sufficiently heated.

Real-time software glances into immediate future

Project manager Sabrina Haase, mathematician at Fraunhofer MEVIS, explains that generating an image of the liver’s position every tenth of a second is in itself not fast enough to reliably direct the ultrasound beam. “This is why we developed software that can see into the immediate future and calculate the next position of the treated region.”The program determines the path for the focused ultrasound waves to reach the liver tumor even when the patient moves while breathing. Developing the software was quite challenging: it must run both highly realiably and in real time.

Another difficulty facing the scientists was the fact that the ribs lie in front of the liver. To prevent the beams from damaging the ribs, elements in the ultrasound transducer that would have hit the ribs were deactivated, much like blocking the holes in a showerhead which spray water in an unwanted direction.

Technical development phase completed

“We have completed the technical development phase and have already run preliminary tests,” Haase says. In the test, a robotic arm moved a gel model back and forth in the MR scanner to simulate the liver movement inside the body. At the same time, the gel phantom was exposed to focused ultrasound, and the MRI scanner monitored the temperature distribution. “The results match our expectations. Now, we can pursue the next steps.”The first TRANS-FUSIMO tests on patients are planned for mid-2018. Thereafter, in cooperation with an industry partner, medical product certification can be tackled. If the method proves itself, in the future, it would be possible to treat other organs that move with breathing, such as the kidney, pancreas, or even lungs.