The company works on apps that turn smartphones into monitoring devices that collect health metrics to diagnose pulmonary function, hemoglobin counts and other critical health information. The company’s apps – including SpiroSmart and SpiroCall, HemaApp and OsteoApp – were under review by the FDA earlier in 2017.

“Those sensors that are already on the mobile phone can be repurposed in interesting new ways, where you can actually use those for diagnosing certain kinds of diseases,” Patel said when explaining what Senosis was about. He declined to comment when contacted by GeekWire on the deal with Google.

How the Sinosis apps work:

Google's healthcare business is logically focussed at least in part on using smartphones as diagnostic tools. Googles mobile operating system Android has a roughly 85 percent worldwide market share. Much of Google's experimental work involves using wearable technology that's connected to people's phones, according to Fortune. It's logical however to the technology that's already in there, particularly when trying to diagnose people remotely, or in situations where additional technology is scarce but smartphones abound.

The other founders of Senosis included Dr. Jim Stout, a professor of pediatrics and an adjunct professor of health services at the University of Washington; Dr. Margaret Rosenfeld, an attending physician at Seattle Childrens Hospital and Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine; Dr. Jim Taylor of the University of Washington, and Mike Clarke, the former associate director in UW’s technology transfer office.

“Those sensors that are already on the mobile phone can be repurposed in interesting new ways, where you can actually use those for diagnosing certain kinds of diseases,” Patel said when explaining what Senosis was about. He declined to comment when contacted by GeekWire on the deal with Google.

How the Sinosis apps work:

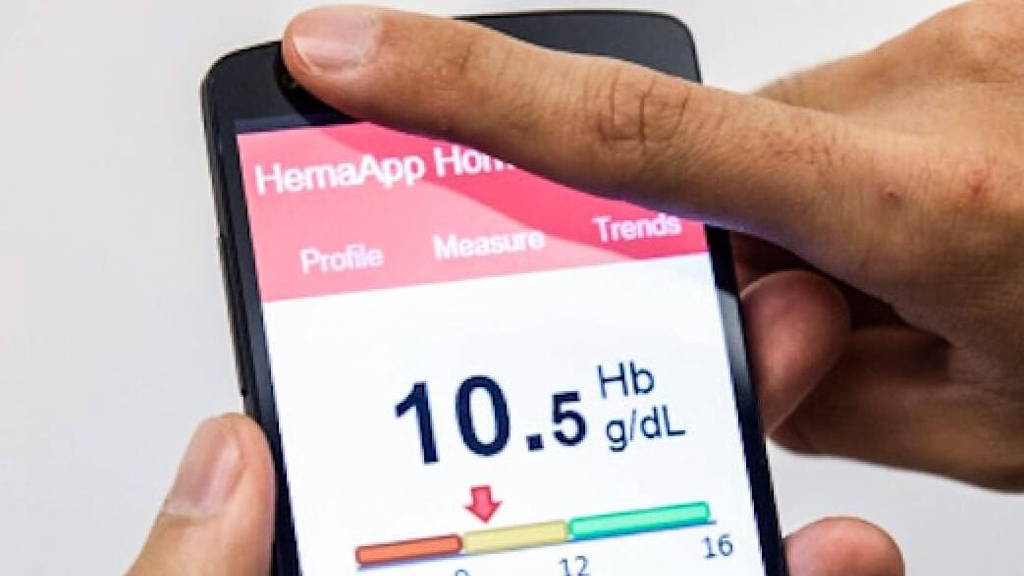

- HemaApp uses a smartphone's camera to measure hemoglobin, in order to detect and help treat conditions such as anemia and malnutrition, without the need for drawing blood. This one does require an add-on, in the form of an LED lighting attachment.

- Bilicam uses the phone's camera and flash to detect jaundice in babies by "examining wavelengths of light absorbed by the skin."

- SpiroSmart and SpiroCall involve people calling a 1-800 number and blowing into their phone's microphone, in order to perform lung function tests.

Googles continued interest in healthcare

The acquisition of Senosis represents Google’s continued interest in the digital health arena, GeeWire writes. In this arena it’s already active, with life science company Verily and AI-deep learing platform DeepMind as foremost representatives. UK based DeepMind was bought by Google some years ago. Verily was launched in 2015, by Google’s parent company Alphabet. Verily was designed to bring together technology, data science and healthcare in a way that would allow people to “enjoy longer and healthier lives.”Google's healthcare business is logically focussed at least in part on using smartphones as diagnostic tools. Googles mobile operating system Android has a roughly 85 percent worldwide market share. Much of Google's experimental work involves using wearable technology that's connected to people's phones, according to Fortune. It's logical however to the technology that's already in there, particularly when trying to diagnose people remotely, or in situations where additional technology is scarce but smartphones abound.

Senosis management not joining Google

Patel and his colleagues at Senosis are not joining the Verily team. One source told GeekWire that the Senosis team will remain at Google, forming the backbone of a digital health effort based in Seattle. It’s also unclear how much was paid for Senosis, which was in the process of raising a series A financing round from leading venture capital firms when the acquisition offer materialized.The other founders of Senosis included Dr. Jim Stout, a professor of pediatrics and an adjunct professor of health services at the University of Washington; Dr. Margaret Rosenfeld, an attending physician at Seattle Childrens Hospital and Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine; Dr. Jim Taylor of the University of Washington, and Mike Clarke, the former associate director in UW’s technology transfer office.