By intercepting and reverse-engineering signals exchanged between a heart pacemaker-defibrillator and its programmer, the researchers found they could perform a number of things: steal patient information, flatten the device's battery, or even send malicious messages to the pacemaker. These messages can contain commands to deliver a shock or to disable a therapy, and so can be life threatening to patients using the devices.

The attacks the researchers developed, according to Computerworld, can be performed from up to five meters (16 feet) away using standard equipment. With more sophisticated antennas this distance can be increased by tens or hundreds of times, the teams believe.

The researchers in Leuven and Birmingham said they had notified the manufacturer of the device they tested, and discussed their findings before publication. They will present their findings at the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC) in Los Angeles.

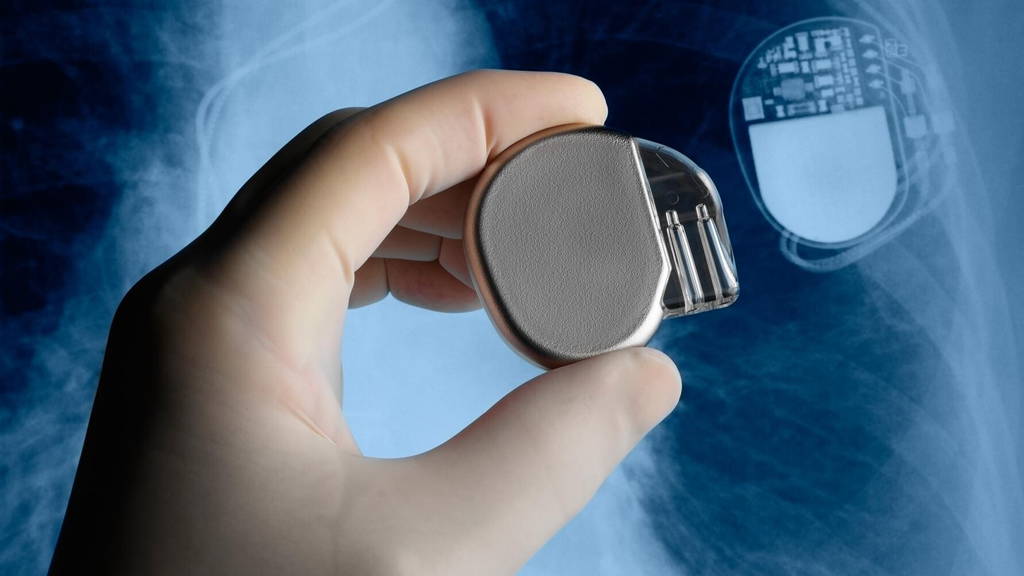

The consequences of these attacks can be fatal for patients, the researchers wrote in a new paper examining the security of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs). These devices monitor heart rhythm and can deliver either low-power electrical signals to the heart, like a pacemaker, or stronger ones, like a defibrillator, to shock the heart back to a normal rhythm.

Among the attacks they demonstrated were breaches of privacy, extracting medical records bearing the patient's name from the device. They also showed how repeatedly sending a message to the ICD can prevent it from entering sleep mode. By maintaining the device in standby mode, they could prematurely drain its battery and lengthen the time during which it would accept messages that could lead to a more dangerous attack.

Until devices can be made with more secure communications, the only short-term defense against such hijacking attacks is to carry a signal jammer. A longer-term approach would be to modify systems so that programmers can send a signal to ICDs, putting them immediately into sleep mode at the end of a programming session, they said.

The Deloitte survey was conducted among 24 hospitals in nine countries in EMEA. It found that over half the hospitals surveyed used standard passwords (i.e. factory settings) to secure their equipment. Almost half the surveyed hospitals also did not know whether their equipment will comply with forthcoming privacy legislation (for example the EU General Data Protection Regulation, meant to replace current regulations starting 2018). Only a fifth stated that the majority of their devices use secure network connections to ensure data reliability and confidentiality.

The attacks the researchers developed, according to Computerworld, can be performed from up to five meters (16 feet) away using standard equipment. With more sophisticated antennas this distance can be increased by tens or hundreds of times, the teams believe.

10 types of pacemaker vulnerable

At least 10 types of pacemaker are vulnerable, according to the team, who work at the University of Leuven and University Hospital Gasthuisberg Leuven in Belgium, and the University of Birmingham in England. Their findings add to the evidence of severe security failings in programmable and connected medical devices such as ICDs.The researchers in Leuven and Birmingham said they had notified the manufacturer of the device they tested, and discussed their findings before publication. They will present their findings at the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC) in Los Angeles.

The consequences of these attacks can be fatal for patients, the researchers wrote in a new paper examining the security of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs). These devices monitor heart rhythm and can deliver either low-power electrical signals to the heart, like a pacemaker, or stronger ones, like a defibrillator, to shock the heart back to a normal rhythm.

Easy reverse engineering

"Reverse-engineering was possible by only using a black-box approach. Our results demonstrated that security by obscurity is a dangerous design approach that often conceals negligent designs," they wrote, urging the medical devices industry to ditch weak proprietary systems for protecting communications in favor of more open and well-scrutinized security systems.Among the attacks they demonstrated were breaches of privacy, extracting medical records bearing the patient's name from the device. They also showed how repeatedly sending a message to the ICD can prevent it from entering sleep mode. By maintaining the device in standby mode, they could prematurely drain its battery and lengthen the time during which it would accept messages that could lead to a more dangerous attack.

Until devices can be made with more secure communications, the only short-term defense against such hijacking attacks is to carry a signal jammer. A longer-term approach would be to modify systems so that programmers can send a signal to ICDs, putting them immediately into sleep mode at the end of a programming session, they said.

Security in healthcare not up to speed

Recently, news was published concerning a hackable thermometer from Johnson & Johnson. And according to a May report on Cyber security of network connected medical devices in (EMEA) Hospitals 2016’ by Deloitte, hospitals are increasingly aware of the importance of good cybersecurity in their medical devices. But improvements are still needed at an operational level.The Deloitte survey was conducted among 24 hospitals in nine countries in EMEA. It found that over half the hospitals surveyed used standard passwords (i.e. factory settings) to secure their equipment. Almost half the surveyed hospitals also did not know whether their equipment will comply with forthcoming privacy legislation (for example the EU General Data Protection Regulation, meant to replace current regulations starting 2018). Only a fifth stated that the majority of their devices use secure network connections to ensure data reliability and confidentiality.