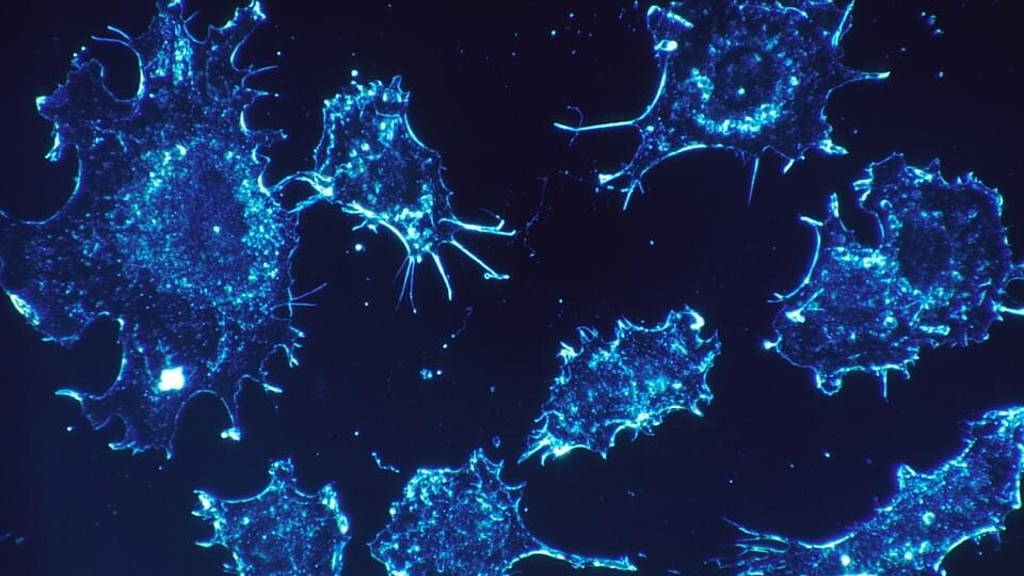

According to the NIBR, phosphatases play a big role in the development of cancer cells. Millions of hours have gone into research on how to take on these proteins, that play an important role in many cell signaling pathways. But recently NIBR researchers caught one of the phosphatases. By means of an out-of-the-box approach they were able to block the SHP2 phosphatases.

The researchers were able to identify several compounds that silence the protein, involved in many cancers, by cementing it shut. The team then showed that this molecular glue kills human cancer cells in mice and wrote about it in Nature on June 29. The tumor-fighting glue is now being optimized for testing in patients.

Pascal Fortin, a corresponding author on the paper published in Nature, tells the researchers took advantage of the fact that SHP2 works like a hinge. “It’s only active when it’s open, and we were able to keep it closed. We’re the first group to find drug-like molecules that can inhibit this important target.”

While the therapeutic potential of a SHP2 inhibitor was clear, the structure of the protein was an important obstacle. The part of SHP2 responsible for its signaling activity resembles the end of a battery, with a massive positive charge that makes things complicated from a drug discovery perspective. Positively charged molecules attract negatively charged molecules, and charged molecules make poor drug candidates. Scientists have discovered many compounds that block SHP2’s active site, but they are all negatively charged.

Using crystallography and mutagenesis experiments, the scientists showed that their compounds were filling a hole in the protein near its hinge, holding everything together. They applied the molecular glue—which had drug-like properties—to mouse models, working with animals that contained human tumors with receptor tyrosine kinase alterations. The cancer cells eventually disappeared.

The researchers were able to identify several compounds that silence the protein, involved in many cancers, by cementing it shut. The team then showed that this molecular glue kills human cancer cells in mice and wrote about it in Nature on June 29. The tumor-fighting glue is now being optimized for testing in patients.

Pascal Fortin, a corresponding author on the paper published in Nature, tells the researchers took advantage of the fact that SHP2 works like a hinge. “It’s only active when it’s open, and we were able to keep it closed. We’re the first group to find drug-like molecules that can inhibit this important target.”

SHP2 plays role in many different cancers

The researchers worked on SHP2 because it plays a rol in many different forms of cancer. First author on the paper Ying-Nan Chen first already proposed SHP2 as a target in 2007 because of this reason. Its an ‘accomplice’ in tumors driven by proteins called receptor tyrosine kinases (such as EGFR, FGFR2, HER2 and ALK). These receptor tyrosine kinases—which are altered in some 30 percent of human cancer cell lines—activate important MAPK molecular signaling pathways that regulate cell growth and division. SHP2 is involved in the activation part.While the therapeutic potential of a SHP2 inhibitor was clear, the structure of the protein was an important obstacle. The part of SHP2 responsible for its signaling activity resembles the end of a battery, with a massive positive charge that makes things complicated from a drug discovery perspective. Positively charged molecules attract negatively charged molecules, and charged molecules make poor drug candidates. Scientists have discovered many compounds that block SHP2’s active site, but they are all negatively charged.

Fresh approach

The researchers took a fresh approach and finally realized that the active site is only exposed when the protein is open. The team designed an unconventional, multi-step chemical screen to find out if the protein could be closed. This led to the discovery of the molecular glue against SHP2.Using crystallography and mutagenesis experiments, the scientists showed that their compounds were filling a hole in the protein near its hinge, holding everything together. They applied the molecular glue—which had drug-like properties—to mouse models, working with animals that contained human tumors with receptor tyrosine kinase alterations. The cancer cells eventually disappeared.