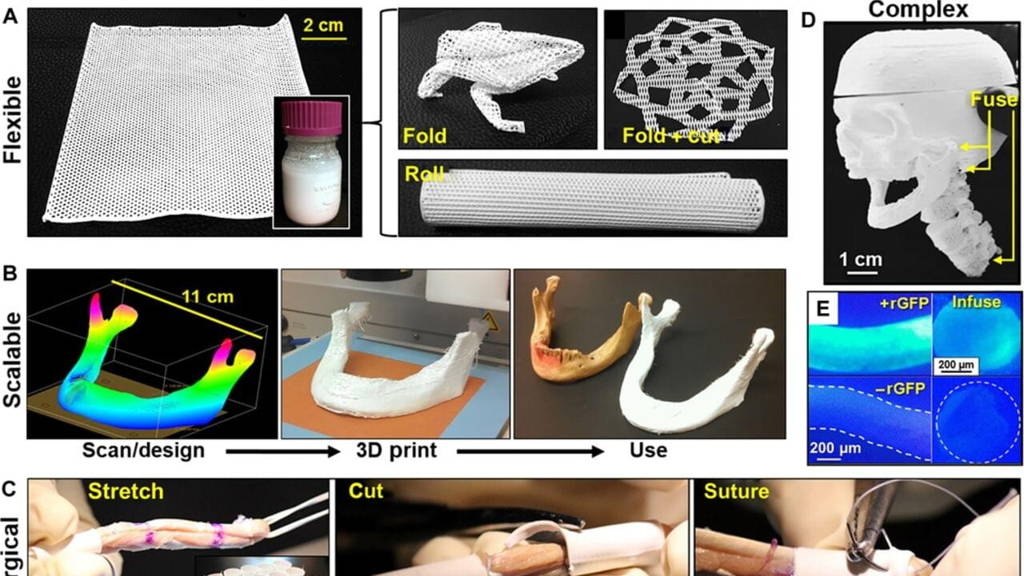

It overcomes many of the current shortcomings, researchers explained in Science Translational Medicine. The new material is strong, elastic and it helps the body regenerate new bone on its own. But the most important characteristic; the material isn’t brittle, which allows surgeons to cut a piece without it crumbling, a common flaw in current synthetic bone constructs.

Researchers used the right combination of starting materials and printed it at room temperature, instead of using heat or lasers, so explains Ramille Shah, principle investigator on the paper and biomaterials scientist at Northwestern University.

Shah’s team added a polymer called polycaprolactone to a bioactive ceramic called hydroxyapatite, which is commonly used in attempts at regenerating bone. Instead of using hot-melt or laser-based 3D printing, the team used a solvent-based, room-temperature 3D printing technique that relied on a unique combination of three solvents.

Doing so, we’ve improved the microstructure of the ink, says Shah. “It doesn’t dry out right away. It’s a little wet which allows each layer to adhere to the previous one,” she adds. They named the substance “hyperelastic bone”.

The printed scaffold integrated well into the animals’ bodies, during the rat and monkey research. The animals’ immune system didn’t reject the implant and blood vessels moved into the porous material quickly. The body’s cells will naturally regenerate new tissue and replace the synthetic scaffold. The material will, over time, biodegrade is the expectation.

These findings could be particularly beneficial to children who need bone grafts, because it essentially grows with the child, says Adam Jakus, a postdoc in Shah’s lab and an author of the report.

Before it can be tested on humans, it requires a lot more testing and development. Shah wants to have clinical trials within five years. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved a 3D-printed substance for use as a regenerative bone material, Jakus says. They hope hyperelastic bone will be the first.

Researchers used the right combination of starting materials and printed it at room temperature, instead of using heat or lasers, so explains Ramille Shah, principle investigator on the paper and biomaterials scientist at Northwestern University.

Shah’s team added a polymer called polycaprolactone to a bioactive ceramic called hydroxyapatite, which is commonly used in attempts at regenerating bone. Instead of using hot-melt or laser-based 3D printing, the team used a solvent-based, room-temperature 3D printing technique that relied on a unique combination of three solvents.

Doing so, we’ve improved the microstructure of the ink, says Shah. “It doesn’t dry out right away. It’s a little wet which allows each layer to adhere to the previous one,” she adds. They named the substance “hyperelastic bone”.

The printed scaffold integrated well into the animals’ bodies, during the rat and monkey research. The animals’ immune system didn’t reject the implant and blood vessels moved into the porous material quickly. The body’s cells will naturally regenerate new tissue and replace the synthetic scaffold. The material will, over time, biodegrade is the expectation.

These findings could be particularly beneficial to children who need bone grafts, because it essentially grows with the child, says Adam Jakus, a postdoc in Shah’s lab and an author of the report.

Before it can be tested on humans, it requires a lot more testing and development. Shah wants to have clinical trials within five years. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved a 3D-printed substance for use as a regenerative bone material, Jakus says. They hope hyperelastic bone will be the first.