Whether we talk about telemedicine, telecare, metaverse, wearables or other breakthrough technologies, the starting point for considering their implications for care is what connects us: trust between individuals. Having someone "tinker" with your body requires you to submit to that person's expertise. The confidential connection ("trusted link") is the starting point for being able to receive and deliver care.

Before I, as a doctor, can help my patients, we must be able to tune in to each other. For example, if I am counseling someone, I need a lot of input for my actions. I can only achieve this by thoroughly reviewing the patient's health data, recognizing the expectations, and then matching them with my capabilities in terms of my expertise, knowledge and experience.

Conversely, the patient must be able to tune in to me: how the development of the disease is expected, how I evaluate this development, and how I evaluate it as facts from the medical records and from what I experience when we are in contact. What possible treatment might mean for him/her in a particular situation, and what are my additional recommendations?

Longing for values that have been forgotten

By being able to adapt to and communicate with patients seamlessly, you make a big difference as a doctor. This is the most important skill of a Data-Driven Doctor: the ability to tune into the other person. However, it requires altogether abandoning prejudices, thinking outside the biases, and putting yourself in the patient's position by literally "walking in their shoes." This is no soft skill; this is professionalism. To open up to the other person, trust is essential. There is a reason why consultations take place behind doors: confidentiality. No matter how many performance and quality indicators are developed, the real value lies in a thorough understanding of the person seeking help.

Frequently heard terms such as "empathetic doctor," "patient-centricity," "shared-decision making" seem to make it painfully clear that today's situation leaves much to be desired and needs to change. Knowledge, experience, and expertise are one thing; the other is how it is applied to the patient during the visit.

Even more surprising is that these skills are often considered soft in medical practice. The current model promotes doctors with a business-like approach equipped with hard medical knowledge. However, paradoxically, medical knowledge is not only the information acquired at the university, from books or research papers but also that gained by observations and being open to the other person.

Reconciling science with empathy

Knowing each other well, what each other's expectations and experiences are – and being open to each other and to improving communication – a trusted relationship is built. Unfortunately, this is where we lag behind. Strange, isn't it? When you want a haircut or a change in hairstyle, you go to your favorite and trusted barber. You know that they will understand and implement your idea of self. What about a visit to the doctor?

The clinical course is key to gaining knowledge about personality and illness, how they are presented and reported, and how and if you can respond to them as a doctor. How can you facilitate the patient's control over their own health? Can you reduce some of their worries and sometimes – even if for a short time – take them over? At the same time, as a doctor, you never take off your clinical glasses. You honestly, but with empathy, communicate the facts, the diagnosis, the implications for the patient and the options on the table.

Digital enabler for doctor-patient synergy

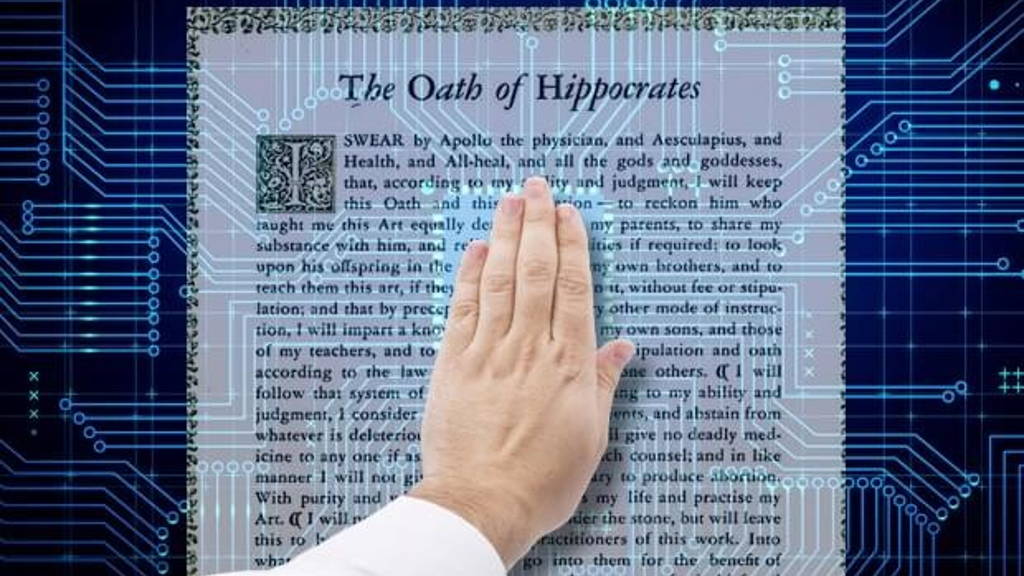

This foundation is the basis of care rooted in the Hippocratic Oath. It cannot be measured or legally defined. It cannot be put in the form of checklists or quality control.

It is a purely human element of the medical profession, in which mutual trust clearly determines the success of therapy.

In this confidential context, ethical dilemmas are solvable, however pronounced and painful they may sometimes be. It is now up to us to seize this opportunity and not leave it to a few to determine how we want to deliver and receive (digital) care.

If we go back to the core values of the doctor making a promise to the patient and society of the best health and care under conditions of confidentiality (the Hippocratic Oath), the data-driven doctor and his patient (society) lead the technology and take care of the information, including digitally.

It starts with a matching process between doctor and patient, open communication that relies on a trusted connection as a requirement for information (data) to be valuable.